Postmortem: Valen the Rogue in the Domain of Darkness

Why did it take me so long to write one short story?

Starting projects is easy. Being the kind of person who starts projects, doesn’t indicate at all whether you’re the kind of person who finishes them. There’s a saying which goes something like “the first 90% takes the first 90% of the time, and the last 10% takes the other 90% of the time.”

Finishing a project is an entirely different skill than starting one.

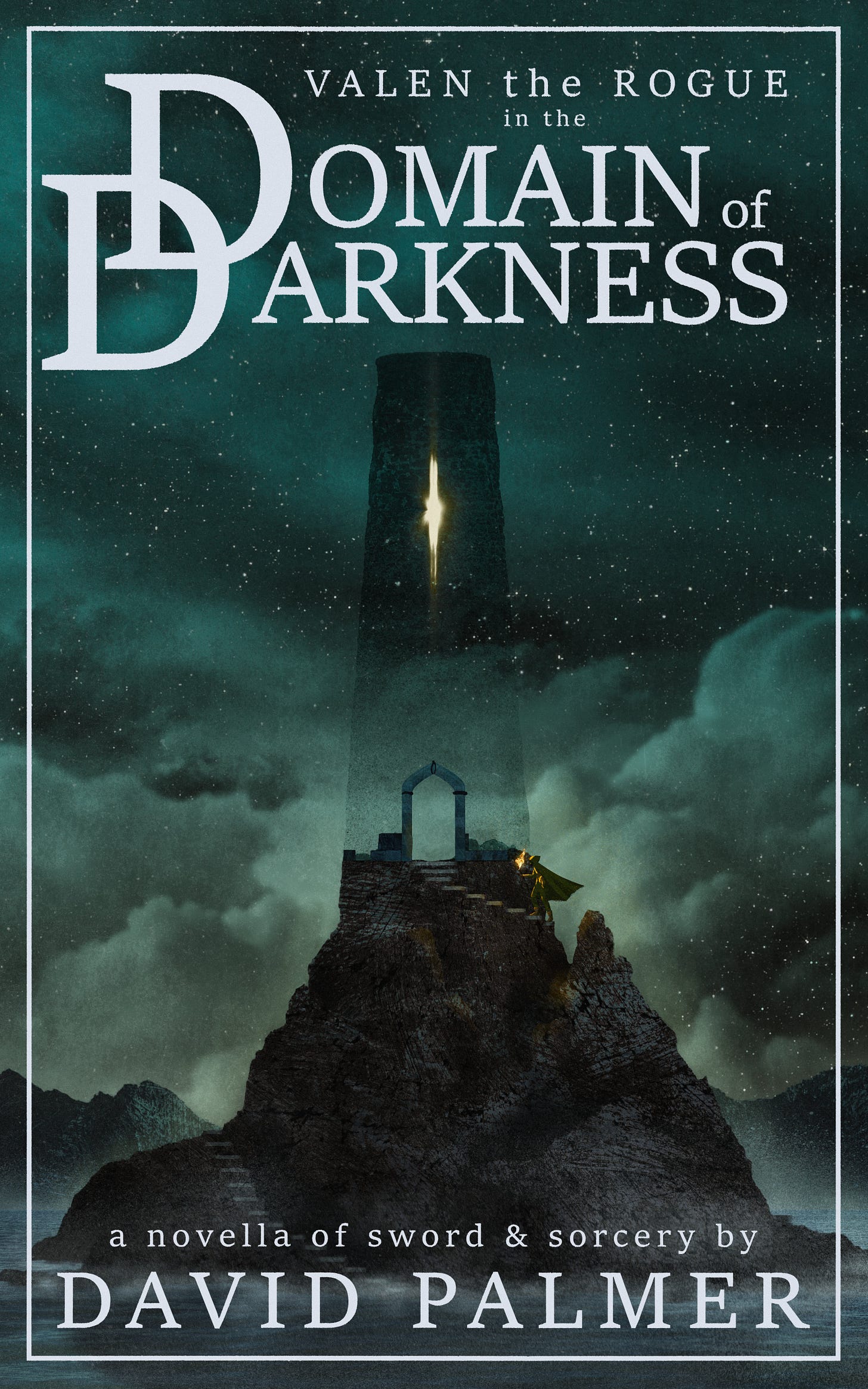

Valen the Rogue in the Domain of Darkness is hardly my first creative writing project. In fact, it’s not even the first Valen the Rogue story I attempted to write. I’ve sat down with a blank document on many occasions and started writing the beginnings of stories doomed never to conclude. Sometimes I’ll spend no more than an afternoon on them. Occasionally I’ve chipped away for years. The end result is always the same.

So in the interest of becoming a better writer, and pursuing my goal of publishing something worth reading, I decided to commit to something smaller.

⛔️ Eliminating Analysis Paralysis

Starting this project required a bit of a silent, personal commitment. I decided that if I spent my free time on anything creative at all, it would be this. Having so few free moments, especially as a parent, leaves no room for deciding what to do with what little free time you’re afforded. And lots of room for deciding to not really do anything at all.

There’s a certain self-discipline required for such a commitment. New ideas are more exciting than old. So making the commitment requires acknowledging that the time spent may be less fun. Less relaxing.

But that’s the cost of completing a creative project, as far as I can tell.

📉 Devaluing Ideas

Frankly, I didn’t have any ideas that would fit into a short story. I had big ideas. Series of novels ideas. Ideas too big to see clearly just how big they are. And I was emotionally attached to those ideas, for no good reason other than the fact that they were mine.

What I needed were ideas I didn’t care about. Ideas that were small… barely interesting enough to turn into a story, let alone spiral out of control into something unmanageable.

I ended up coming up with several short story ideas suitable for a fantasy setting with relatively low stakes. Low, at least, compared to the likes of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, wherein the world (or more!) is repeatedly on the verge of terminal disaster. These were ideas that could be executed without tons of world building, as a short story doesn’t allow for much of that. And they were stories whose plots would be interesting enough absent grand arcs which tease sequel after sequel.

To take things even one step further, I took one of the ideas that seemed almost too simple to execute: that of a thief robbing a sorcerer’s really, really dark tower.

📝 Back to the Word Doc

So I did what anyone would do and opened up a new document, stared at the blank page, and started writing something that sounded like the opening to a story.

✋🏻 There are two big problems with this!

The first problem is that writing prose (i.e. the words themselves, the ones that describe what happens) is an entirely different discipline than coming up with a story (i.e. the ideas of what happens, why, to whom, and then what happens next).

If that doesn’t make sense, imagine tasking everyone who watched the same play with writing it out as a short story afterward. The plots (stories) would be similar, if not nearly identical, but the words (prose) each person would use would be entirely different. There would be as many versions of the same story as there were members of the audience!

The second problem is that our minds are uneven, and tend to gloss over things in ways we’re not conscious of. Stories are also uneven. But their unevenness comes in the form of pacing, wherein important and interesting things may be given more room on the page, and unimportant and uninteresting things less.

These two sets of uneven terrain do not naturally overlap in a helpful way. The result of this is that as the story progressed, pieces of it which I had spent more time imagining beforehand took up a lot of words, and pieces which I’d “saved for later” ended up being too short, even if they were important.

🧻 First Draft

My goal of 10,000 words snuck up on me before I knew it. Not in that it came too quickly; just the opposite. I slogged forever through the draft. But in that when I reached the goal, the story was underdeveloped. The setup was nearly 7,000 words, the action and payoff were about 3,000.

That’s not an ideal distribution.

10,000 words is plenty of time in which to tell a simple story, especially if you adhere to the advice of beginning as far into the action as you reasonably can, and ending as promptly as possible. I thought I had done both. But it was still a mess.

🗑️ Second Draft

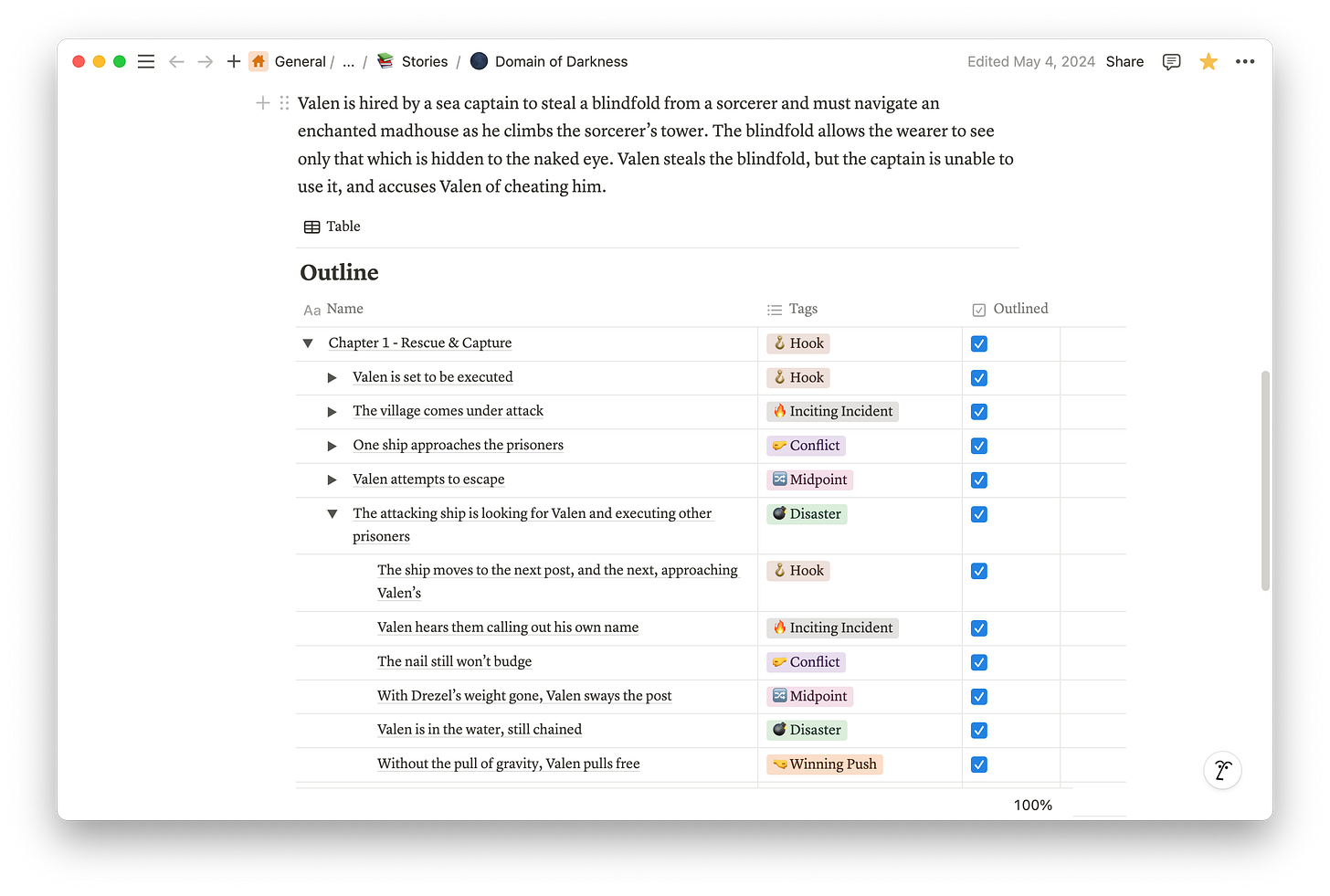

The second time around, I decided to take a more methodical approach. I’d outline the story first, and then build on that outline. I wasn’t ready to commit to something like the Snowflake Method. But I knew that just putting one word after another wasn’t giving me the result I wanted.

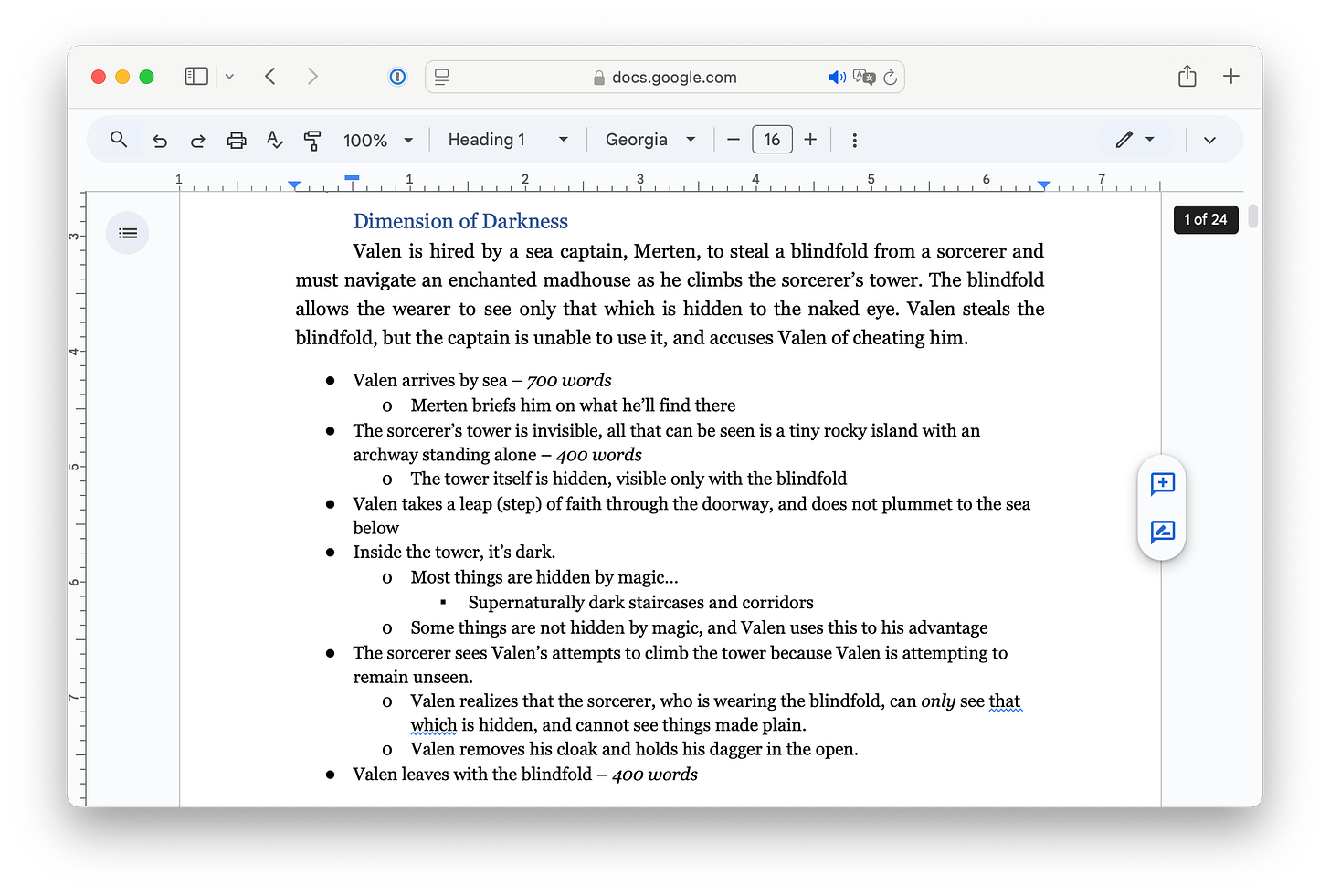

This is clearly a very rough outline. I’d done little more than try to break apart what I already had and attempted to budget a word count for every part. And I didn’t even finish it. Despite being equipped with such a simple plan, the second attempt was went much smoother than the first.

All told, outlining turned out to be the creative writing equivalent of when you’d tell your teacher that your essay was “already done” and you “just needed to type it up.” Except it’s true.

But the story still wasn’t any good… Maybe I’m just not a great writer. That’s entirely possible. But I still knew I could do better.

📃 What is a Story?

It’s remarkable that even after spending so much time consuming stories, it’s possible (and even likely) that you may not know what makes a good story. Or any story for that matter. I’d heard of the three act story structure. But that’s still pretty vague. You can break a story into those parts but can you assemble one from them? Maybe. I decided to go all the way back to the basics and ask “how does a person write a story?”

Calling something a story has very little to do with how long it is. Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time series is a story, and it’s more than four million words long. Children are famous for telling stories of similar length with next to no point whatsoever. But people don’t read the Wheel of Time because it’s only interesting if you commit to all fourteen books. They read it (or any story for that matter) because it’s engaging book by book, chapter by chapter, scene by scene, and yes, even sentence by sentence.

Here’s the thing. Tons of people have spent their lives thinking about this. There’s no end to the advice you can find online about what makes a good story. There are even outline templates detailing how much time a writer should spend on each story beat. The rules for writing an interesting big story and an interesting scene are about the same. And, after some searching, I found a set of rules that described a kind of generic structure for a story that I thought sounded good enough to imitate.

The Internet is seemingly full of writers who churn out full-length books multiple times per year. Nearly all of them say they outline more. Now it was my turn.

Unfortunately, outlining after the fact was difficult, as the story was already written. Trying to fit something that already existed onto a structure I didn’t originally have in mind was a challenge. And even though I’d picked a loosely-defined idea I didn’t care about very much, by this point I was invested in this story, and retrofitting it into someone else’s structure meant sacrificing ideas I liked.

I suspect it’s impossible to commit yourself to an idea you don’t care about. You’ll likely wind up caring.

Budgeting words, as with money, allows a certain freedom within the confines of that budget. The pacing of the story is more or less locked in. Now, instead of needing to fill a certain number of pages, the ideas need to be written succinctly enough to fit within those pages. It may be a matter of mental gymnastics, but I found that only being able to use one page to get a scene across is a different matter entirely than having to figure out how to say enough to fill up a whole page. More often than not, I’d (unintentionally) write twice as much and then boil it down to what I needed after. Following the guidance of what I’d planned in my 343-point online, there was simply too much story and not enough time. So I expanded my goal to about 24,000 words - squarely in novella territory - and attempted again.

Surprisingly, after agonizing over the outline for ages, the draft was finished before I knew it.

⏭️ What Next?

The process was far from perfect, and involved a lot of repeating the same work multiple times over. For my next project, I’ve continued with what worked for me, and left behind what didn’t. And although it’s been the better part of a year since Domain of Darkness was first released on Amazon’s Kindle store, I am pleased to say that it has taken far, far less time to write its sequel, Valen the Rogue and the Starlit Scepter.

I look forward to launching the prerelease for Starlit Scepter very soon.

🔌 Shameless Plug

The subject of this post, Valen the Rogue in the Domain of Darkness, is available on Amazon as an eBook and in paperback.